By stepping up whenever she saw an unmet need, Julie De Vries has positioned herself to be a uniquely equipped advocate for children and mental health.

At first glance, the career path of Julie (Seeley) De Vries appears to zig and zag from one area of expertise to another with no rhyme or reason. On closer inspection, it’s clear she has spent decades putting together all the pieces of a puzzle society doesn’t always like to acknowledge. With backgrounds in education, law and clinical mental health counseling, De Vries (’94, ’95) is uniquely suited to help children and families during difficult times. She provides play therapy and counseling, as well as continuing education in trauma, attachment and foster care.

“Coursework for my bachelor’s in family science piqued my interest in advocacy for children and families,” she said. “The focus on child development formed a foundation to which I added knowledge with additional degrees and experiences. A liberal arts background set the stage for lifelong learning.”

Her career metamorphosis started after De Vries earned her Master of Arts in Education and was working as the director of the University’s Child Development Center. Through experiences with one of the students, she learned about foster care and child advocacy in the legal system and felt inspired when she interacted with one of the children and their legal representative.

“I thought, ‘I could do that.’ One night I told my husband out of the blue I wanted to go to law school,” she said.

After earning a law degree from Drake University, De Vries started her private practice. She returned to small-town Iowa one year later and continued to practice law while also serving part-time as judicial magistrate in her hometown of Centerville. In private practice, she represented a lot of young legal clients, and combined with her educational background, she knew a supportive resource was lacking in the area – play therapy. Using play as a medium, children are able to express their thoughts and emotions, allowing them to process experiences, understand their feelings and develop coping skills. While play therapy is a widely accepted form of treatment, the required training and commitment to ongoing education can make it difficult to find service in rural communities.

“I represented a lot of young legal clients who did not have access to play therapy,” De Vries said. “The nearest play therapist was a half-hour drive away. I thought, ‘I could do that.’”

After earning a degree in clinical mental health counseling, De Vries is now the only certified play therapist in her county, and one of only a handful in the region. It is one more skill she can add to her counseling and consulting firm, and something that gives her an advantage in helping clients.

“Mental health, law and education merge and overlap frequently in my practices,” she said. “For example, I can speak the language of individualized education plans when I collaborate with schools regarding play therapy clients. I can also utilize the language of parent-child therapy when I attend a team meeting with my legal client regarding plans to reunify her with her child. Knowing the vocabulary of juvenile law is helpful in mental health counseling with an adult client who has involvement with a state agency regarding the safety of her child.”

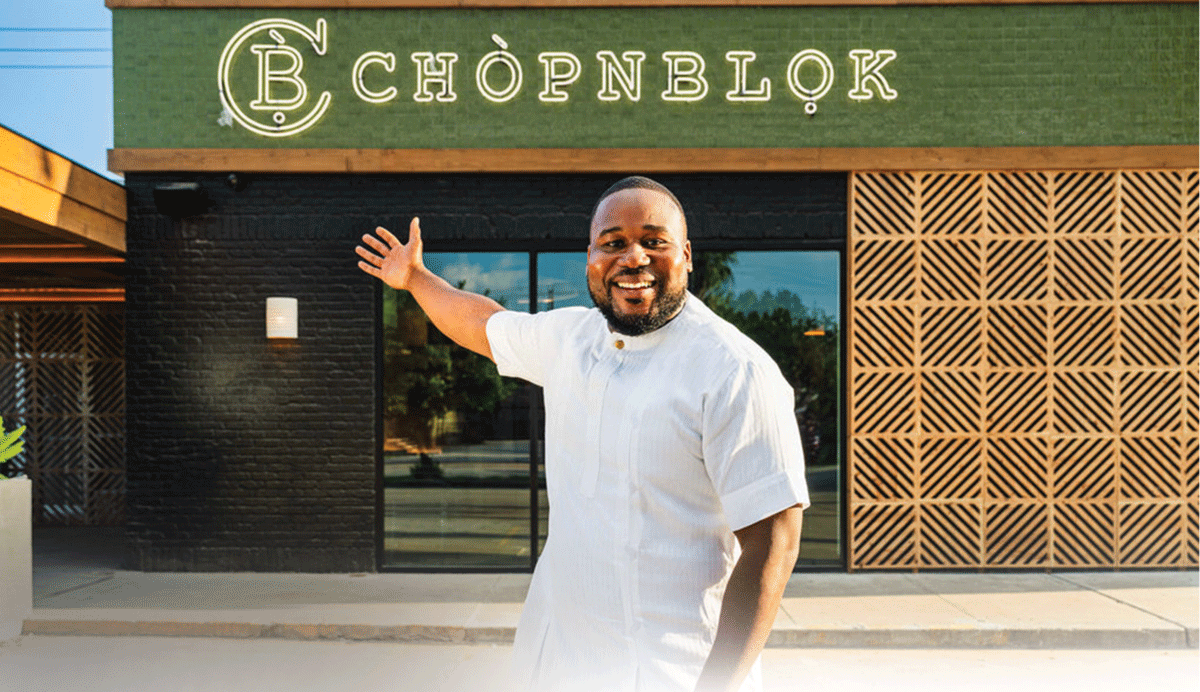

Julie and David

De Vries’ work can be as varied as her background. She often consults with parents/guardians and schools, providing assessments both informally through her practice and formally in reports to courts. Some days she can be found conducting on-site counseling services at a therapeutic school, and other days she may be in court serving as a guardian ad litem or as an attorney for children in juvenile law, family law or victims in criminal law. De Vries has even argued a case in front of the Iowa Supreme Court. While there may be many lenses with which to view a court procedure or counseling session, she tries to keep a core tenet in mind for everyone involved.

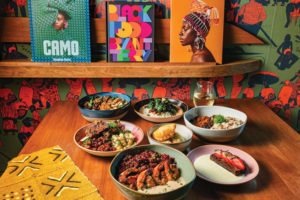

Sadie and Julie

“Many times, clients are doing the best they can with the situation and skills they have. It’s easy to judge people without knowing the background. I promote giving grace to individuals who struggle,” she said. “Compassion promotes healing.”

Not every client De Vries interacts with starts in the legal realm. Much of her counseling work is intervention-based support, usually in service to the whole family. The goal is always to match the right treatment with each client. She may see some clients for only a few weeks if they are struggling with a short-term issue. Sometimes, educating clients on the goal is the first step of the process.

“Understanding of trauma and its effects on individuals is expanding into other professions; however, counseling services are still somewhat stigmatized,” she said. “I try to normalize mental health treatment by emphasizing the health aspect and not the symptoms.”

Support for families doesn’t stop for De Vries at the end of the workday. She and husband David (’03) are a licensed foster care family. They have provided respite care as well as full-time placements, and they adopted their daughter Sadie through the foster care process. She joins brother Levi in rounding out the De Vries home in Centerville.