Remembering World War II and Those Who Served

The atmosphere on campus in the late 1930s and early 1940s was an interesting mix of anxiousness and obliviousness. War loomed, and while the general consensus was that the United States would eventually become involved, many on campus chose not to think about what was in store.

“There was a feeling it was coming, especially in ’40 and ’41,” Gerald “Shag” Grossnickle (’42) said. “The main thing was, ‘Let’s have a good time while we may. We might not live to see tomorrow.’”

Attendee Harvey Young shared the same outlook.

“I didn’t worry about it too much,” he said. “I was probably having too much fun.”

For the most part, day-to-day life on campus went largely unchanged until 1941. Grossnickle remembers being on the dance floor in Kirk Auditorium with his future wife when he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“I knew we were at war then,” he said. “There was no question.”

According to “Centennial History of the Northeast Missouri State Teachers College,” written by President Emeritus Walter H. Ryle, fall enrollment for 1941 was 846. By comparison, just three years later only 302 students remained. In 1944, only 101 degrees were awarded and women were the recipients of 82 of them.

Traditional fixtures of college life faded away for a time. The football team skipped three seasons of play, and in 1942 Ryle announced the University would not celebrate another Homecoming until after the war.

In Kirksville, one of the early indicators that war was inevitable was the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPT) sponsored through the government. The University began participation in the program in January 1941. While the goal may have been to train civilian pilots, by 1943 the program had officially changed to the War Training Service. The participants were on a strict military regimen and lived in barrack conditions in Kirk Building.

Even though the program took place on campus, many of the men involved were not University students and some came from various states all across the country. In his book, Ryle estimates the University helped train anywhere from 1,800 to 2,000 men during the school’s three-year participation in the program. One of those trained in the early days of the program was William “Bill” Minor (’42).

“I got my license there just before World War II started in 1941,” he said.

Minor enlisted in the Army Air Corps and was commissioned after his graduation. He, Grossnickle and Young are just a few of the individuals with University ties that served. Their stories, while unique in their own rights, do share similarities and are emblematic in several ways of the many alumni, students, faculty and staff members who participated in the war effort.

For Minor, although he was a licensed pilot, he spent much of his first year and a half of active duty gaining training experience stateside. Before he even got out of the country, he was exposed to just how dangerous the task at hand would be. On a training flight in Florida, his squadron of aircraft encountered a tropical storm and five pilots perished. That was just a taste of some of the misfortune he would see and experience.

Upon entering the Army Air Corps, Minor had hopes of being a fighter pilot. He was even scheduled to fly the famed P-51 Mustang, but a shortage of bomber pilots forced a last-minute change of duty that left him piloting a B-24 for the Eighth Air Force. While he may have been disappointed in the reassignment, it was not all bad for Minor. He was taught to fly the B-24 by Hollywood legend Jimmy Stewart. Also, while conducting training exercises in Iowa, he met his future wife of nearly 65 years.

* * *

Young, like his childhood friend Minor, got his pilot’s license through the CPT. He attended the University for three years and was working at a company that manufactured airplane parts in Wichita, Kan., when he was accepted into the Army Air Corps. He gave up a job that paid $1,000 a month in order to serve.

“We all had the idea we had to do it,” he said. “It was our duty.”

By the end of the war, Young would have more than 1,700 hours of flight time in combat zones in the Pacific, primarily transporting cargo, food, medical supplies and troops. On his first mission in theater, his flight came under attack over Rabaul, Papua New Guinea.

“Flak was so thick you could walk on it, but luckily we didn’t get hit,” he said.

After getting his plane turned around, he had to fly through a weather system to escape. A lightning strike knocked out the electrical systems and the crew had to make a dead reckoning heading back to Guadalcanal. It would not be Young’s last brush with death.

“I thought, ‘By God, what have I got myself into?’” he said.

Despite living in a war zone, dealing with heat, mosquitoes and what he describes as awful food and drinking water, Young does have some fond memories of his service time. On regular runs to Sydney, Australia, his ability to secure bottles of whiskey ultimately led to him winning the favor of a two-star general and at times serving as his personal pilot. Occasionally, he was responsible for flying in entertainment from the USO, and although he did not personally transport him, Young got to spend one evening sharing drinks with Bob Hope.

* * *

Grossnickle also had some memorable moments awaiting his final orders for the war. In the fall of 1942, he was in Rhode Island preparing to go overseas with the Navy. The St. Louis Cardinals happened to be playing in the World Series against the New York Yankees, and he and his wife were able to take a train into the city to catch a game.

Fortune smiled on Grossnickle more than once while he was in Rhode Island. Due to another sailor’s illness, Grossnickle was reassigned at the last minute to the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago. He would spend the duration of the war stateside training countless regiments of sailors before they were sent overseas, eventually working his way up to battalion adjutant. After about a month in Chicago, Grossnickle received word that the group he was previously assigned to, and would have remained with if not for the last-minute switch, had been shipped out and every one of them had been killed.

“I think it was the grace of God that I was the last one to come to Chicago,” he said.

* * *

The defining moment in Young’s flying career came when he was transporting a group of military police and fighter pilots out of Okinawa to Manila. At one point in the trip, the squadron flew into a typhoon. Past the point of no return, without enough fuel to go back and flying in an area where lower altitudes were controlled by Japanese forces, Young had no choice but to go through the storm. Although he found a hole to fly through at about 10,000 feet, the trip was anything but ideal. At times he could not see, and the storm was so intense it ripped off several pieces of the plane.

“I never took such a ride in my life. It just tore us to pieces,” he said. “I thought we weren’t going to make it.”

At one point, he considered ditching the plane over water, but knowing what that meant for everyone’s chance for survival, he pressed on through the storm. After nearly half an hour of white-knuckle flying so intense that both his navigator and co-pilot got sick, as did most of the troops being transported, the plane broke out of the weather. As fortune would have it, they came out of the storm and immediately found an emergency landing strip on the island of Luzon that was not on the navigator’s map.

“The good Lord just built us an airstrip,” Young said.

It was not until he was safely on the ground that he fully realized all he had been through.

“Luckily, I was so scared that I didn’t get sick in the air,” Young said. “When I landed, I was just so scared I couldn’t sign the form you are supposed to sign.”

Damage to the plane was severe enough that it was later junked, but all aboard made the trip unharmed. According to Young, a similar plane flying just 10 minutes behind was not as lucky. It went down in the jungle and was not found until the 1970s.

* * *

Although he was an experienced pilot by the time he landed in England in November 1943, Minor would not rack up a tremendous amount of flight time during the war.

“I only flew five missions,” he said.

On Jan. 5, 1944, during a bombing run over Kiel, Germany, Minor’s plane came under attack from Axis forces. Three German Luftwaffe fighters repeatedly strafed the plane. Minor lost contact with the crewmembers in the rear, and when his B-24 no longer returned fire, he knew those men were already killed or injured. The German planes then focused their attack near the front cabin where he was located, eventually striking the engine, causing it to burst into flames.

“I knew I had to get out,” Minor said. “The plane was on fire and it was coming up on the flight deck right behind me.”

As flames overtook the airplane, Minor could hardly see. He had to take a leap of faith, hoping the plane’s bomb bay doors were still open, leaving him an escape route. Luckily for him, they were.

“I just plunged right through the fire and went right through the bomb bay doors,” he said.

Just a few seconds passed between the time Minor exited the aircraft and when it exploded. He and two fellow crewmembers came down in the frigid waters of the North Sea at the bay entrance to the Kiel Canal. While they were fortunate enough to hit a sandbar at low tide, they landed within sight of a group of Hitler Youth accompanied by German soldiers and were immediately apprehended.

A fourth crewmember was unable to get out of the plane before it blew up, but was fortunately blown out of the wreckage and his parachute opened undamaged. He was severely burned, but made it to land and was later transported to a hospital. Six of the 10 crewmembers were killed in the attack.

Minor and the two others spent a week at an interrogation center before being packed into a boxcar with approximately 200 other prisoners of war. They spent two days on a train without any regard for food, water or sanitation. One night was spent in a Berlin rail yard, and bombing runs from British forces nearly sealed their fate. Eventually they would end up at a camp near Barth, Germany, where they would spend the remainder of the war.

Minor has a “war room” in his home where he keeps mementos from his service time. When asked, he freely discusses his experiences, but the details of his imprisonment are not among the stories he likes to share.

“I don’t much want to talk about that,” he said.

Despite spending nearly a year and a half in the prisoner of war camp, Minor maintains a relatively positive outlook on the world.

“Life is too short to be bitter,” he said.

* * *

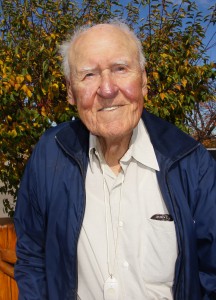

All three men came home after the war, and by nearly any measurement, each has led a charmed life.

Minor and his wife Dolores had four children. He would spend 38 years as a faculty member of the University in the industrial education department, and he also devoted several years to the Air Force Reserve. A man of many interests, he has enjoyed dancing and writing, as well as researching the war. Through connections he made online with a man in Germany, he now owns a piece of the wreckage of the plane he bailed out of seven decades ago.

Although not an employee of the University, Young also stayed in Kirksville and maintained strong ties to the school. He had a successful career in banking and volunteered his services as a treasurer for the University for more than 20 years. He and his wife Jane had two children and were married for more than 50 years before she passed.

Grossnickle was married to his wife Sarah for almost 70 years before her passing, and the couple had three children. Since his time in the service ended, Grossnickle has become a jack-of-all-trades. He taught for a year, ran a restaurant for a while and spent a total of 28 years in elected office serving the citizens of Adair County in various capacities. During an eight-year stint as the sheriff, he never carried a gun, rarely wore a uniform and often kept his badge in his pocket. He also bought a share in an insurance company, which he would later go on to own and operate with one of his sons. He still maintains a desk in its office.

“I don’t work, I visit,” he said.

If that were not enough, Grossnickle was named a Master Conservationist by the Missouri Department of Conservation for his efforts to bring wild turkey to the region, and he is a member of six different halls of fame, including the Truman Athletics Hall of Fame and the Missouri Athletics Hall of Fame.

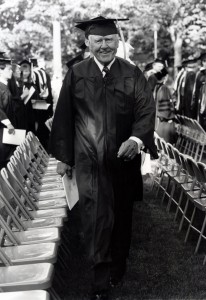

For all his accomplishments, Grossnickle had only one regret. Because he was called into service, he never got to walk across the stage and receive his degree. That was remedied in 1993 when he was invited to participate in summer commencement ceremonies.

“It was a great feeling. I had my whole family there to watch that,” he said. “It was a thrill. It eased the disappointment.”

* * *

While other military conflicts have come and gone, perhaps none of them have affected the campus community as much as World War II. The University did not keep official records of military service at the time, so an exact number of those who served might never be known. The 1945 yearbook published the names of 910 alumni and former students, as well as faculty and staff members, who participated in the war. When considering the number of veterans who enrolled for the first time after their service, the number of participants with University ties is probably incalculable today.

Outside the entrance to the Ruth W. Towne Museum and Visitor’s Center, four bronze plaques bear the names of University members who made the ultimate sacrifice during World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. The names on the World War II plaque double that of the Vietnam War plaque in terms of lives lost. Grossnickle, Young and Minor are each humble about their roles during the war, and they know they are among the lucky ones to have returned.

“I made a lot of good friends here in college,” Grossnickle said. “A number of them didn’t come back.”