A Tradition of Teacher Education

Long before the colors of purple and white were adopted in 1902, or the bulldog was made the school’s mascot in 1915, the University already had a well-established history. Above all else, it was a place to train teachers for public schools.

Much has changed since Truman’s founding—most notably seven different names and the distinction of becoming the state’s only public liberal arts and sciences university—but the development of public educators has remained a cornerstone of the institution. Among the University’s nearly 59,000 living alumni as of fall 2014, a full 25 percent earned either a Bachelor of Science in Education or a Master of Arts in Education.

Discussion about methods to prepare future educators has been a constant topic on campus, almost since the school’s first days. A look back at Truman’s history in regards to its education program will show it was always in flux, but every massive change or minor adjustment was made with quality in mind, both for the future teachers and the field in general.

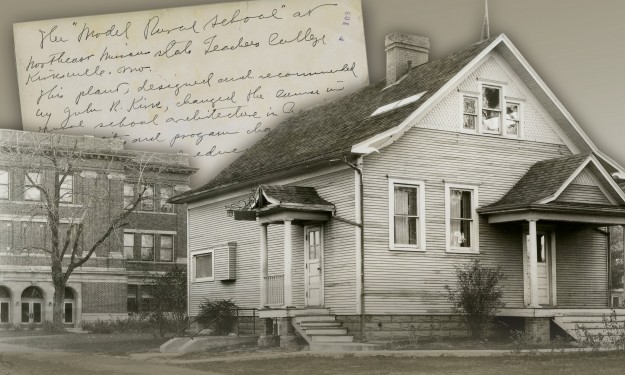

While Truman has been the preeminent University in northeast Missouri for the better part of two centuries, it owes a debt of gratitude to a well-intentioned, but short-lived, learning institution. Cumberland Academy was established in Kirksville before the Civil War and while it never flourished as a school the structure attracted the attention of Joseph Baldwin, a professional educator with years of service as a teacher and administrator.

While Truman has been the preeminent University in northeast Missouri for the better part of two centuries, it owes a debt of gratitude to a well-intentioned, but short-lived, learning institution. Cumberland Academy was established in Kirksville before the Civil War and while it never flourished as a school the structure attracted the attention of Joseph Baldwin, a professional educator with years of service as a teacher and administrator.

In the late 1860s, Baldwin was the president of a private seminary school in Indiana, and he had a desire to create his ideal school. In addition to the availability of the Cumberland Academy building, family ties and the urging of education leaders in Missouri helped sway the Pennsylvania native to establish his school in Kirksville. The North Missouri Normal School and Commercial College opened its doors in 1867, and just three years later it was Missouri’s first state-supported institution of higher education established for the primary purpose of preparing teachers for public schools.

Baldwin believed the basic education of a teacher should be a thorough program of both arts and science. To earn a bachelor’s degree, his educational program required 120 semester hours between mathematics, sciences, languages, English, literature, history, political economy and professional education. Fifteen men earned state teaching certificates as the Normal School’s first graduating class in 1870.

After Baldwin stepped down as president in 1881, two of his next three successors brought some differing opinions on how to approach teacher education. In Joseph Blanton’s nine-year reign, he shifted the focus more towards the academic side of the curriculum and less towards teaching others how to teach. William D. Dobson followed Blanton, and he seemed to take an almost opposite approach, focusing on the art of teaching rather than academics.

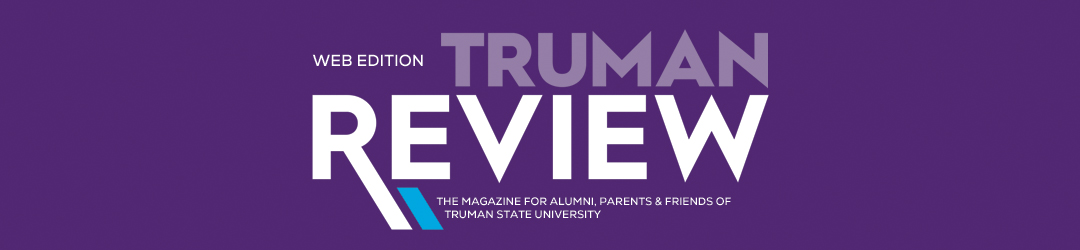

With the arrival of John R. Kirk in 1899, the school returned more to the idea of broad-based education for teachers. However, he did more than just reestablish Baldwin’s philosophies. Kirk was interested in helping to improve the facilities and quality of education in many of Missouri’s rural schools, and he was instrumental in establishing the model rural school. Just as Baldwin had a vision of his ideal college, Kirk had dreams of a perfect schoolhouse, which he built on campus in 1907. The Demonstration Rural School would serve students as well as future educators for 10 years before being repurposed during World War I.

“The Model Rural School exemplified the simplest, yet most complete, practical and economical architecture ever devised anywhere for rural or village schools and the most effective facilities for instruction use in schools of corresponding grades anywhere,” Kirk wrote in 1910.

“The Model Rural School exemplified the simplest, yet most complete, practical and economical architecture ever devised anywhere for rural or village schools and the most effective facilities for instruction use in schools of corresponding grades anywhere,” Kirk wrote in 1910.

One former model school, which can also be seen as an example of the evolving approach to teacher instruction, is the Ophelia Parrish Building. Constructed in 1923 and named in honor of the former supervisor of the practical school, the building was a model school for a number of years before later serving as the local junior high school. Although model schools have been phased out over the years, the spirit and practicality of them remains. When Eugene Fair assumed the presidency from Kirk, he implemented a cadet system of teaching that required teachers in training to work for three months in a nearby community in an effort to expand and enhance their laboratory experiences. While the cadet system was discontinued in 1932, the idea of integrating education students into community schools is still in place. Currently, Truman students are active in several schools throughout the state completing their observation hours and conducting student teaching.

“We want students to stay connected with their dreams of becoming teachers, and they need to have the experience of working in schools as undergraduates,” said Peter Kelly, chair of the Department of Education.

Perhaps the biggest—and most controversial—change for the University in regards to producing teachers was the decision to phase out the Bachelor of Science in Education in the early 1990s. While it may seem strange for a University that started as a normal school to no longer offer an undergraduate degree in education, the switch to an MAE-only option is another example of how Truman tries to stay at the forefront of teacher education.

“Truman has a long and successful history in teacher education. Our job now is to build on that,” Kelly said. “I would say that the quality of our education program, students and teacher preparation has been enhanced by Truman’s transition to a public liberal arts and sciences university. Earning an undergraduate degree in a discipline provides expert content knowledge that serves as the foundation for strong careers in teaching.”

“Truman has a long and successful history in teacher education. Our job now is to build on that,” Kelly said. “I would say that the quality of our education program, students and teacher preparation has been enhanced by Truman’s transition to a public liberal arts and sciences university. Earning an undergraduate degree in a discipline provides expert content knowledge that serves as the foundation for strong careers in teaching.”

Because the elimination of the Bachelor of Science in Education followed a few years after the University mission change in 1985, many people closely associate the two. However, the seeds for an MAE approach were actually sown nearly 50 years earlier during Walter H. Ryle’s presidency. Ryle was one of the biggest proponents of keeping teaching as a central component of the University, so much so that he was opposed to dropping the word “Teachers” from the school name. In the late 1930s he was already exploring how to better prepare teachers, and in a memo to the Board of Regents he mentioned the prospect of additional education.

“I think it’s only a matter of time before the leading teacher colleges of this country will be offering three years above the two years of general education. In other words, instead of having four years of college work as we have today, we will have five years, and at the close of this five years of work a master’s degree in teaching will be granted,” Ryle wrote.

Students interested in the MAE must apply for entry into the program, usually during their senior year. Once in the program, they receive additional coursework in the major area as well as coursework specific to the MAE. Students can get their undergraduate degrees in any number of subjects if they plan on pursing elementary or special education at the master’s level. Those that specialize in the content areas of history, music, science, math, English or a foreign language obtain undergraduate degrees in those disciplines prior to enrolling in the MAE program.

Students interested in the MAE must apply for entry into the program, usually during their senior year. Once in the program, they receive additional coursework in the major area as well as coursework specific to the MAE. Students can get their undergraduate degrees in any number of subjects if they plan on pursing elementary or special education at the master’s level. Those that specialize in the content areas of history, music, science, math, English or a foreign language obtain undergraduate degrees in those disciplines prior to enrolling in the MAE program.

Today, Truman produces roughly 100 MAE graduates per year, and while that number may seem small in comparison to the 500 Bachelor of Education graduates per year the University was turning out nearly a century after its founding, it is more a representation of the shifting interests of the student body than a reflection on the University’s regard for educating teachers. Since its inception, the University has built upon programs it was already offering in order to provide more degrees to those not necessarily interested in teaching. Normal schools alone are a thing of the past. Baldwin’s first students were already studying a variety of subjects, so it was a natural progression for the University to serve more students. While more education students were being turned out at the 100-year mark, they were already accounting for a smaller percentage of the graduating class.

Another factor that can be lost in looking only at numbers is the quality of preparation. While Truman may not produce as many education graduates as it did in the past, arguably it still turns out better-prepared educators than other institutions.

“Research clearly demonstrates that good teachers have rich content knowledge,” Kelly said. “If you want to be a good teacher, it helps to know your content well. Programs that offer a bachelor’s degree in education offer their students much less content knowledge preparation.”

Proof of the quality preparation Truman education students receive might best be seen in the opportunities they are afforded either during their internships or early in their careers. In addition to internships throughout the state of Missouri, Truman is a partner with the U.S. Department of Defense and MAE students have been able to conduct their student teaching on American military bases in foreign countries. Of late, Truman has also cultivated a growing reputation for its participation in the U.S. Fulbright Program, one of the most prestigious exchange programs in the world. Several Truman MAE students or alumni have gone on to spend time teaching in various locations around the globe, including two this year.

Proof of the quality preparation Truman education students receive might best be seen in the opportunities they are afforded either during their internships or early in their careers. In addition to internships throughout the state of Missouri, Truman is a partner with the U.S. Department of Defense and MAE students have been able to conduct their student teaching on American military bases in foreign countries. Of late, Truman has also cultivated a growing reputation for its participation in the U.S. Fulbright Program, one of the most prestigious exchange programs in the world. Several Truman MAE students or alumni have gone on to spend time teaching in various locations around the globe, including two this year.

In addition to the countless teachers specializing in history, music, science, math and languages, Truman MAE graduates have gone on expand the boundaries of the education field. They can be found spreading their knowledge in a variety of fields, including outdoor education, culinary arts and journalism among many

more. MAE graduates are also well prepared to continue their own educations and several have gone on to

receive a Ph.D.

The fact that so many Truman-trained teachers are practicing their crafts in more non-traditional roles is further evidence the University’s approach to education instruction is working. Another indication of success is Truman alumni earning back-to-back Missouri Teacher of the Year awards (sidebar, page 17).

“Deep and rigorous content knowledge, coupled with an emphasis on reflective practice, ensures that Truman MAE teacher candidates are well prepared to meet the unique challenges facing today’s educators,” said Janet Gooch, dean of the School of Health Sciences and Education.

With so many different philosophies of education instruction, it can be easy to take sides, but the reality is all of the competing ideas of past presidents have helped to shape where the University is today. Their contributions did not jockey for position as much as they coalesced, and remnants of their philosophies still can be seen. Baldwin’s belief in a broad-based education is a core principle to the school’s liberal arts mission. Blanton would no doubt be pleased with Truman’s high academic standards and the reputation the University has garnered since his tenure. Ryle’s vision of a master’s degree requirement and Charles McClain’s ability to make it become a reality show a commitment to the art of teaching for which Dobson would certainly be proud. Additionally, glimpses of Kirk’s desire to use the University’s resources as an avenue to improve the community can be seen in the many service-learning projects conducted by current students and faculty members, as well as the observation hours and teaching internships that take place throughout the state.

With so many different philosophies of education instruction, it can be easy to take sides, but the reality is all of the competing ideas of past presidents have helped to shape where the University is today. Their contributions did not jockey for position as much as they coalesced, and remnants of their philosophies still can be seen. Baldwin’s belief in a broad-based education is a core principle to the school’s liberal arts mission. Blanton would no doubt be pleased with Truman’s high academic standards and the reputation the University has garnered since his tenure. Ryle’s vision of a master’s degree requirement and Charles McClain’s ability to make it become a reality show a commitment to the art of teaching for which Dobson would certainly be proud. Additionally, glimpses of Kirk’s desire to use the University’s resources as an avenue to improve the community can be seen in the many service-learning projects conducted by current students and faculty members, as well as the observation hours and teaching internships that take place throughout the state.

Predictions about the future of education in America can be hard to make. Certification requirements, changing curriculums, technological innovations and shifting budgets are just a few of the factors at play, and no one knows for sure what skills the teacher of tomorrow will need in the classroom. Baldwin could not have foreseen chalkboards giving way to smart boards, or inkwells becoming obsolete and Wi-Fi hotspots becoming a near necessity. While those things happened, they did not diminish Truman’s ability to produce quality educators, and there is no reason to think future changes should sidetrack the University either.

“Technology, state and federal requirements, the learning environment, pedagogical methods, globalization—those all influence education and are constantly changing and evolving,” Gooch said. “The MAE program needs to stay abreast of these changes and the impact that they have on teacher preparation. Truman will continue to produce high-quality teachers that meet the needs of the local area, the state and the nation.”

Editor’s Note: Some of the information for this article was taken from “Centennial History of the Northeast Missouri State Teachers College,” by Dr. Walter H. Ryle and “Founding the Future: A History of Truman State University,” by Dr. David C. Nichols.